Exploring Neanderthal intelligence: An unprecedented examination of their cognitive abilities

In a groundbreaking discovery, a new study from Australia, published in "Archaeological and Anthropological Sciences", suggests that Neanderthals had more complex tool production skills than previously thought. The study, which focuses on the Levallois technique, a method used by Neanderthals 200,000 to 400,000 years ago, reveals that Neanderthals deliberately controlled the striking angle of their tools.

The conscious control of the striking angle in tool production is at the center of the study. Previously, it was assumed that the geometry and rigidity of the core primarily determined the shape of the detached flakes. However, the new research contradicts this assumption by showing the influence of the striking angle on the shape of the flakes.

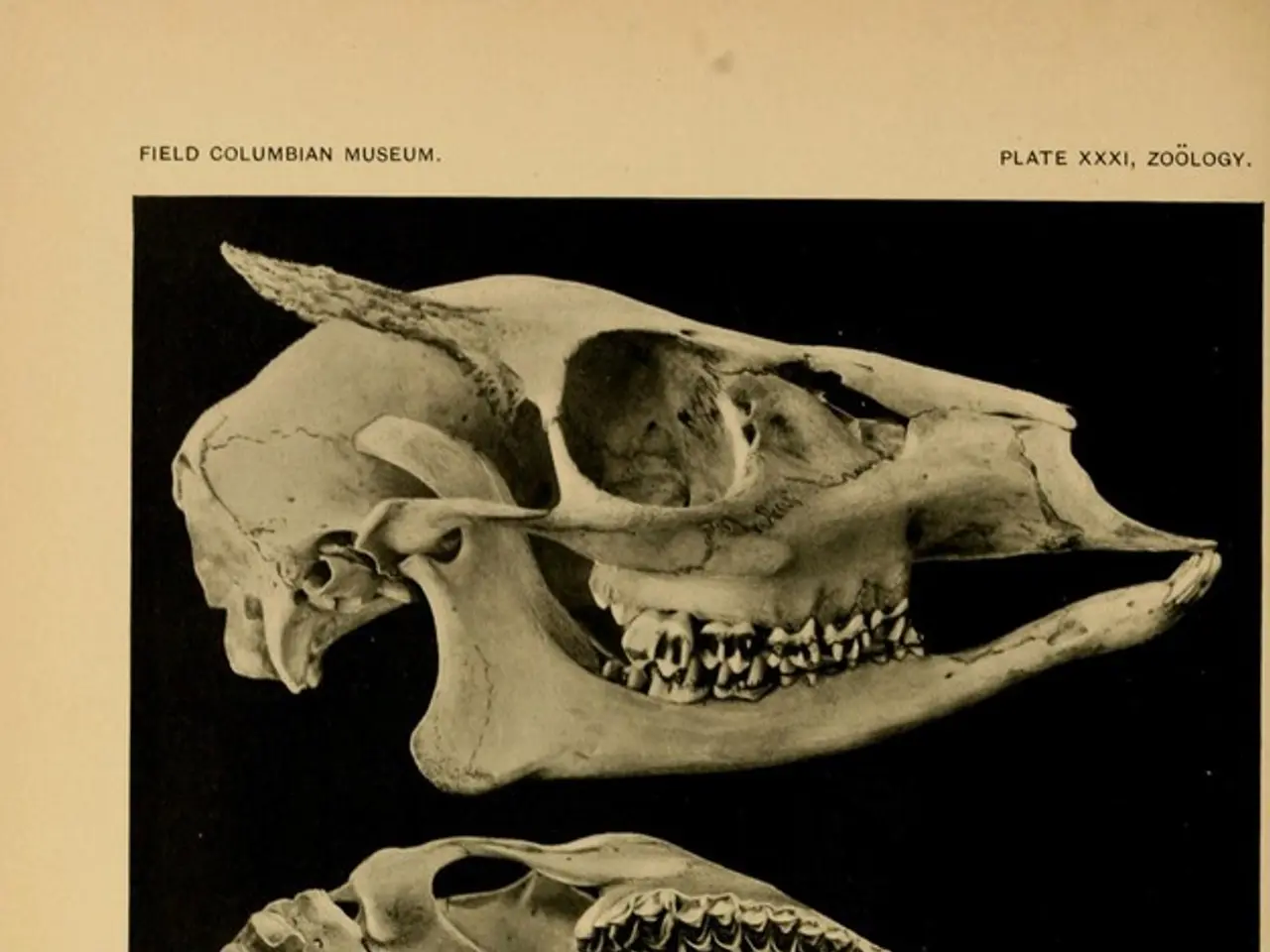

The study used high-resolution 3D scans and cross-sectional analyses to measure and examine the resulting flakes. It was found that flatter striking angles resulted in larger, thicker, and heavier flakes, while steeper angles produced thinner, narrower forms. Moreover, the type of fracture also changed based on the striking angle: Flat impacts created deeper cracks that removed more material from the core, while oblique impacts resulted in more superficial fracture paths.

The conscious control of the strike angle in the Levallois technique could be understood as an expression of a kind of technical intelligence previously attributed only to Homo sapiens. This control over the angle at which they struck stone cores was fundamental for producing the predetermined flake shapes characteristic of the Levallois technique, indicating advanced planning and motor skills in tool manufacture.

Researchers recreated the Levallois technique using stone cores and automated hammering devices to test the effects of different striking angles. The results showed that Neanderthals adjusted their strikes actively and responded to changing conditions, requiring careful assessment of the material and fine-tuning of the strike angle.

The study provides evidence that Neanderthals possessed the ability for foresight and situational adaptation. Instead of the shape of the flakes adapting "automatically" to the properties of the core, independent of the type of force applied, the study suggests that the striking angle was a conscious, controlled variable in the production process.

The Neanderthal's technical understanding is being reevaluated. The significance of Neanderthals' control of the striking angle in the Levallois technique lies in their precise technological skill and cognitive ability to shape stone tools effectively. This control over the angle at which they struck stone cores was fundamental for producing the predetermined flake shapes characteristic of the Levallois technique, indicating advanced planning and motor skills in tool manufacture.

While the search results do not detail the Australian study explicitly, the emphasis on the angle control corresponds to broader evidence that this aspect of the Levallois method was a learned and carefully developed skill among Neanderthals, not just random flaking. The Australian research likely highlights the importance of this control as a marker of Neanderthal technological expertise and cognitive capabilities.

It is worth noting that Levallois technology itself appears widely across different Middle Paleolithic contexts, showing that this control may have been a shared intelligence trait among several hominin groups, including Neanderthals. However, the Australian study adds to the growing body of evidence suggesting that Neanderthals were more technologically advanced than previously thought, challenging the assumption that Homo sapiens were the only ones capable of such sophisticated toolmaking techniques.

Science has unearthed a new discovery about medical-conditions and technology, as it reveals that Neanderthals had a level of technical intelligence comparable to Homo sapiens. Evident in the Levallois technique, Neanderthals demonstrated a deliberate control over the striking angle of their tools, a skill thought to be exclusive to humans. This control was fundamental in producing predetermined flake shapes, highlighting their advanced planning and motor skills in medical-condition treatment and technological advancement.