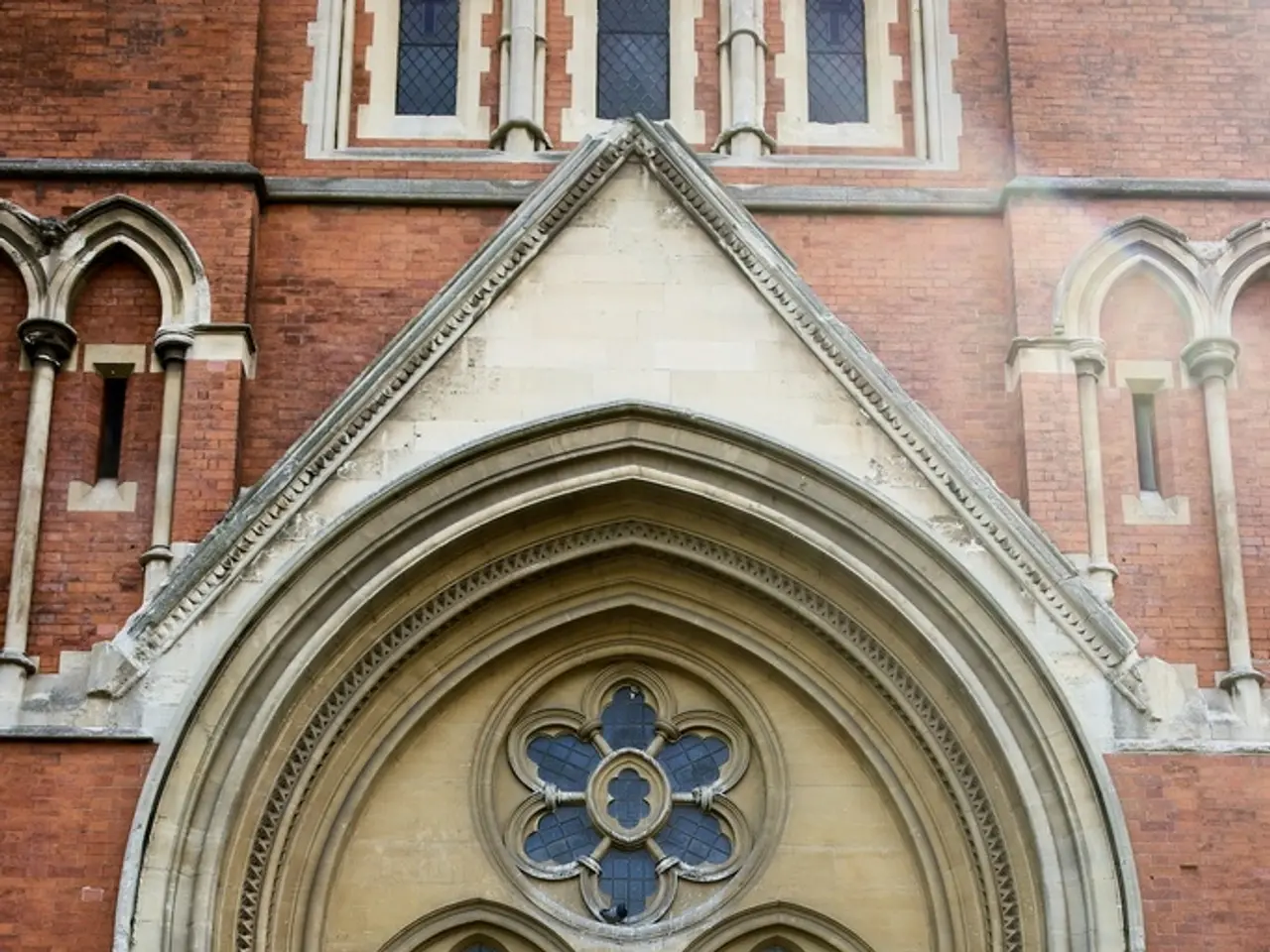

Inquiry: What constitutes a tin tabernacle?

In the early 19th century, a new architectural style emerged in Britain - the corrugated iron church, or as they were more commonly known, tin tabernacles. These unique structures, with their distinctive wavy roofs and iron walls, were a response to the growing need for places of worship in industrial areas.

The first building to employ this innovative design was the turpentine shed at the London Docks, constructed around 1830. However, it was not until 1846 that the Port Glasgow firm of John Reid & Co. built an even more remarkable structure. This iron ship, complete with a large shed on top, could accommodate up to four hundred people.

By the mid-1800s, tin tabernacles were springing up across the country. One such church was the Church of St Paul in the village of Strines near Stockport, built in 1880 to cater to the spiritual needs of workers at the nearby calico print-works. This church, sixty feet long, 21.5 feet wide, and twenty-three feet to the ridge, could seat 200 people.

However, these churches faced a significant challenge - the corrugated sheets were made from wrought iron and quickly corroded. Disaster struck on Christmas Eve 1880 when the Church of St Paul in Frimley Green caught fire, causing damage estimated at around £250. By April 23, 1881, the church had been repaired and restored, albeit at the expense of the stained glass windows.

The corrosion issue was addressed in 1837 when French engineer Stanislav Sorel devised a method of coating the iron's surface with a layer of zinc, increasing its resistance to corrosion. This process, known as galvanization, was introduced to Britain by Commander HV Craufurd RN, who patented it and erected the world's first galvanized buildings in 1844.

Despite the corrosion issues, many tin tabernacles have stood the test of time. Historic England reports that there are approximately 86 remaining tin tabernacles in England, with fewer than twenty being listed. One such listed tin tabernacle is the Church of St Paul in Strines, designated as Grade II listed in 2011. Remarkably, it still serves as a place of worship.

In her research for a Master's dissertation on the conservation challenges of tin tabernacles, Harriet Suter claims to have found 157 tin tabernacles. These structures, while not as grand as some of the more traditional churches, have played a significant role in the history of British architecture and continue to do so today.

One interesting example is the 'floating church', anchored near Strontian on Loch Sunart, Scotland, and used as a place of worship until 1869. These humble structures, made of corrugated iron, have left a lasting impact on the landscape of Britain, standing as a testament to the ingenuity and adaptability of the people who built them.

Read also:

- Koenigsegg sets new 0-400-0 km/h world record, improving previous time by 2.5 seconds.

- Launch of Sustainable Entertainment Alliance's Guidance for Tracking Production Emission Rates, backed by Bafta Albert

- UK successfully conducts DLT-based foreign exchange peer-to-peer trials with three European central banks

- Leading Rolex Models for Women in 2024: Elevate Your Style with These Stunning Timepieces